I'd be curious to see reader opinions on the article and on the likely end of football, a sport I played growing up and have enjoyed watching as an adult.

Theater of Pain

This NFL season has been defined by people talking about "the injury issue" — pundits, columnists, league officials. The one voice you haven't heard — until now — belongs to the players.

By Tom Junod

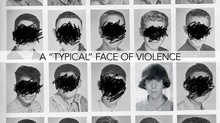

Crushed Skull, Phil Toledano

Published in the February 2013 issue, on sale any day now

My left knee has been aching this entire week. I don't know why. I didn't get hit directly on it in the last game. My right knee has started the week so sore the side where the nerve got hit. When I wear the brace, my knees feel like total crap. When I start moving around, the muscles and tendons in my leg feel so stressed, sometimes I feel they might rupture. My lower back is so sore, painful and stiff; my right shoulder has lost some mobility for some reason. My right ankle is constantly being twisted; my left feels very weak. It's hard for me to react to movement, or even drive off of it. I used the word "hard" but the real word is "next to impossible." I don't sleep much, I feel super stressed, and on game day I take tons of drugs...—An entry from a journal kept by an NFL player for the purpose of preserving, for his children, a record of his painIn 2009, Willis McGahee, then a running back for the Baltimore Ravens, caught a pass in a playoff game — a championship game — against the Pittsburgh Steelers. The pass, from his quarterback Joe Flacco, was perfect. McGahee, known since his days at the University of Miami for his ability to catch the ball, had come out of the backfield and was heading straight upfield, ten yards beyond the line of scrimmage. He did not have to slow down. He caught the ball over his inside shoulder at full tilt. Ryan Clark, a safety for the Steelers, was waiting for him.

It was a big play in a big game, and it turned out to be decisive. The Steelers had just gone ahead, 23 — 14, on a Troy Polamalu interception return. Now the Ravens had the ball on their own twenty-six-yard line, second and six, late in the fourth quarter. McGahee caught the pass just beyond the thirty-five; with two steps, he was just short of the forty. He never got there. Clark gathered himself, then uncoiled. He simultaneously turned and lowered his shoulder, and from a kinetic crouch he extended himself into McGahee, straightening out while leaning forward, leaving his feet after discharging all his energy, his legs helicoptering off to the side. It was a high but legal hit, and the thunderclap it released was definitive, high and low at the same time, a deep pneumatic clang, the sound of a cymbal turned by force into a gong. Clark fell to his side, holding his helmet in his hands as if to stop the ringing in his ears. McGahee fell loosely on his back, where he stayed, his cleats in Boot Hill position, toes to the sky.

"Oh, what a hit! Ball's out, recovered by Timmons. Ryan Clark is still down, so too is Willis McGahee. And they say fumble recovery, Pittsburgh..."

It was not a posture to which McGahee was unaccustomed. Six years earlier, in his last game at the U., he blew up his knee, an injury that was routinely called "gruesome" and "grotesque" and that still enjoys an Internet afterlife as one of the "Top Ten Worst Sports Injuries of All Time." Now he was on the receiving end of one of the signature collisions of the NFL's head-injury era — an era ushered in by a combination of athleticism unfolding at the edge of human capability, the expanding authority of neuroscience, and the horror stories of middle-aged football heroes descending into depression, dementia, and derangement. "When there's a savage hit, you try to get out there quickly," says Dr. Anthony Yates, who for the last thirty years has been the Steelers' team doctor and who currently serves as president of the NFL Physicians Society. "You presume it's a concussion and hope it's not more than that. And when there's two men down, you wonder about the logistics. Are we going to need two trucks, two evacuations...?"

He needed only one. After the familiar spectacle — the familiar American ritual — of two teams heretofore locked in violent struggle crowding the field in solidarity; of solitary players bent in desperate prayer; of television announcers peering through the wicket of medical personnel in order to parse the fallen for "encouraging" signs of movement; of Creedence's "Down on the Corner" playing on stadium loudspeakers for the rowdy and restive crowd: After all this, Ryan Clark walked off the field with a concussion. Only Willis McGahee was immobilized, strapped to a board, and evacuated from the stadium, after which the Pittsburgh Steelers took possession of the ball and the game, on their way to an eventual win in Super Bowl XLIII.

I called McGahee recently. He now plays for the Denver Broncos and was recovering from a torn medial collateral ligament. With the playoffs approaching, and with NFL injuries becoming ever more of "an issue" — the global warming of American sports fans, something to be fretted over and put aside — I wanted to talk to someone whose career has been defined by very public injuries and whose very public injuries have defined the state of football over the last ten years. But he didn't see it that way. "Injury has not been part of my career," he said. "I've only gotten hurt twice. I got hurt once in college and once in the pros."

Right, but that second injury, against the Steelers...

"No. I mean now. The MCL."

"So you don't consider the concussion an injury?"

"That's what they consider it. But getting a concussion and hurting your knee are two different things. You get back up from a concussion."

Willis McGahee was knocked out cold against the Steelers. He went out on the board. He didn't consider himself injured, though, because like all NFL players he considers himself an expert in what qualifies as an injury and what doesn't. The loss of consciousness he suffered in Pittsburgh didn't qualify because it didn't require rehabilitation. It didn't put his career in jeopardy. It didn't exile him from his teammates.

And most of all, it didn't hurt.

McGahee And Clark Collision - Rob Carr/AP Photo

"Fans basically know nothing," Ryan Clark says when asked to talk about his experience of injury. "They know what they see on the field and that's about it. They don't know the work, the rehab, the getting out of bed on Monday morning. A lot of injuries are the ones that don't get reported, the ones that don't take you off the field. People always ask me, 'Are you feeling good?' No. You never feel good. Once the season starts, you never feel good. But it becomes your way of life. It becomes the norm. It's different from a guy going to work at a bank. If he felt like I did, he wouldn't get out of bed. He'd call in."

"Our perspective is our own pain," says the veteran who keeps the pain journal, who we'll call PJ from now on. "What other perspective do we have? We've been beaten down since we were kids that you're never too injured to play. And so when normal people — people who are not associated with football — ask 'How do you feel?' for many years it was hard for me to answer that question. It was hard for me to say exactly how I feel, because it would show a sign of weakness or softness. And at the professional level, you better not say how you feel, or the next man will get your job."

The perspective of pain is what this story is about. For fans, injuries are like commercials, the price of watching the game as well as harrowing advertisements for the humanity of the armored giants who play it. For gamblers and fantasy-football enthusiasts, they are data, a reason to vet the arcane shorthand (knee, doubtful) of the injury report the NFL issues every week; for sportswriters they are kernels of reliable narrative. For players, though, injuries are a day-to-day reality, indeed both the central reality of their lives and an alternate reality that turns life into a theater of pain. Experienced in public and endured almost entirely in private, injuries are what players think about and try to put out of their minds; what they talk about to one another and what they make a point to suffer without complaint; what they're proud of and what they're ashamed by; what they are never able to count and always able to remember.