The is the first installment of a new series from Pacific Standard called The American Man, written by Thomas Page McBee, author of the forthcoming title, Man Alive: A True Story of Violence, Forgiveness and Becoming a Man (City Lights/Sister Spit, September 9, 2014).

This article looks at tattooing as a male bonding ritual. His perspective in these articles (and likely his book as well) is sure to be more interesting than some other male writers on gender - McBee is a transman, and therefore has had to manufacture a sense of masculinity in ways many cis-males have never even considered.

The American Man: A Late Night at Magic Cobra Tattoo

By Thomas Page McBee • June 19, 2014

(Photo: Susan Law Caiz/Shutterstock)

Our constant exploration for a sense of belonging is just about the only thing that could bring Brooklyn hipsters, queers, and a Christian couple from California all together for tattoos in the middle of a full-moon night. That and the $13 price tag.

•

The plan was for the scruffy lot of us to line up at midnight on the 12th outside Magic Cobra Tattoo in Brooklyn to get Friday the 13th tattoos—an underground tradition in shops across the country where $13, tenacity, and whiskey (recommended, not required) gets you a date with a piece of flash chosen last-minute off the shop’s board: a skull with “13” for eyes, a dagger, a toilet on fire.

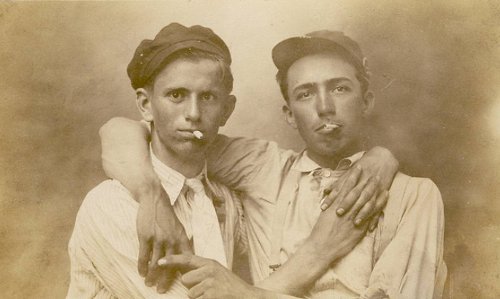

My two buddies and I have dozens of tattoos between us, and there was talk of all three of us getting the same one. A crown, I figured, though I’d go for the owl or a dagger maybe, too. I love my friends, I love reclaiming masculine ritual, and I love tattoos.

What could go wrong?

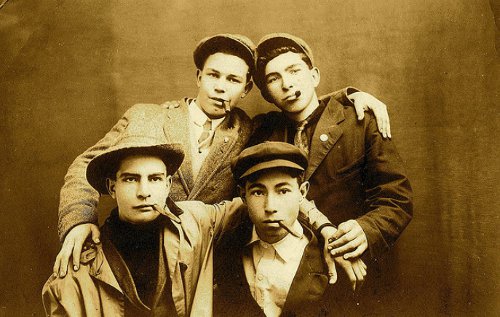

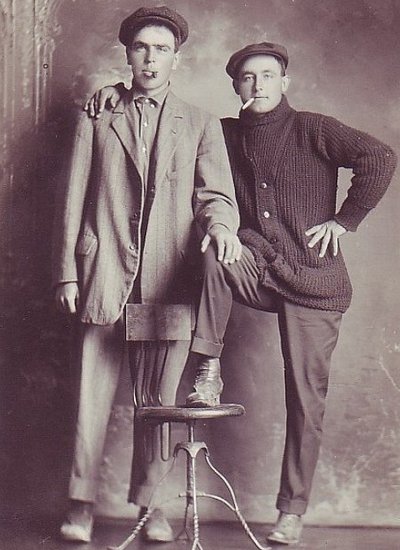

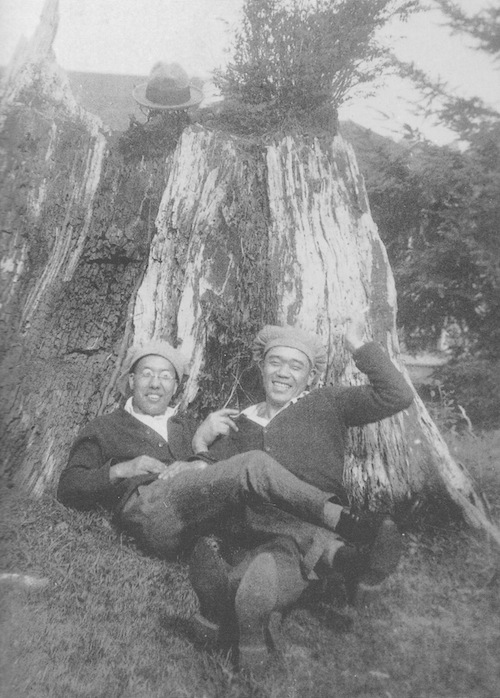

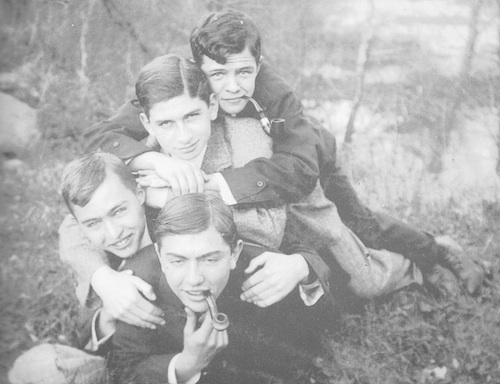

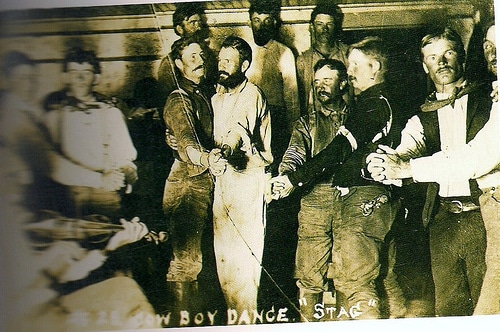

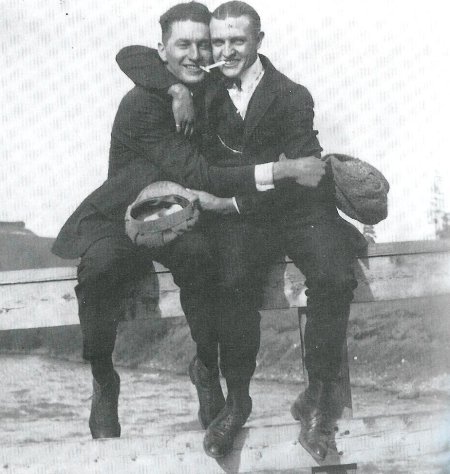

Male bonding traditions are strikingly consistent and problematic in many cultures: often simultaneously homophobic and homosexual, pervasive, historic, and even animal—from skin cutting in Papua New Guinea to foreskin suturing by the Romans to bullet ant-sting initiation in Brazil—they’re also stunning in their commitment to pain and power as a way to mark a masculine coming-of-age.

One dark, modern side of such rituals is hazing—of particular concern in the military and college fraternities. The Army, which defines hazing as “an activity typically steeped in tradition, bound by silence, and ritualistic in nature” that “is thought to mark a transition, celebrate an achievement, or bring someone into a social or professional circle” has a zero tolerance policy for such activities, and the “deadliest fraternity” has eliminated pledging altogether.

I think that’s wise, and the fact is, ever since I began injecting testosterone three years ago, I’ve been drawn to ritual. I didn’t have a boyhood, never stayed up all night at summer camp engaging in harmless pranks like writing “butts” on some poor sap’s forehead, and—like a lot of modern men—I walk a knife’s edge between nostalgia for a true straight razor shave and a gratitude that I can be my tight-jean, literary self without much worry. I’m turned off by the endemic sexism, violence, and homophobia peppering locker room and barbershop talk, and—since I never felt an affiliation with my birth gender—I’m 33 and, for the first time in my life, I experience gender affinity with every toll booth ticket taker who calls me “brother” or “boss.”

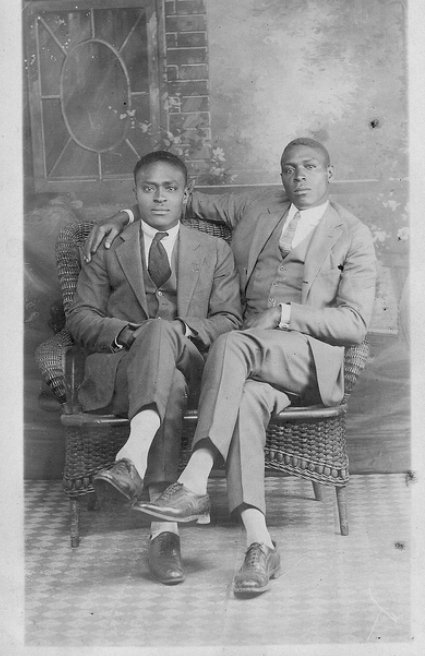

Men are taught that power is the key to relationships, which is where a lot of troubling behavior starts. But an instinct to ritualize bonding may come from a need for healthy belonging. Contrary to popular belief, studies show that under stress that results in vulnerability groups of men (like women) demonstrate cooperative behavior that leads to less aggression and more trust and compassion. So Friday the 13th tattoos with my buddies felt more goodtime portside sailor than, you know, frat nightmare kidnapping and death. That was the idea, anyway.

It was only right that the night started off with my good buddy’s first trip to Shake Shack. We ate burgers and talked about this horrible dude we both want to punch in the face and the women we love, tenderness and red meat and elaborate fantasies regarding this guy getting his comeuppance. Then he bailed on the idea of tattoos so he could get up early enough to meet his fiancée in Philly (“I get it,” I said, because I did), and I took the G to hold a spot in line for my other friend.

The parlor line was a culture all its own. Hardcore old tattoo dudes; Brooklyn hipsters; and a mishmash of twentysomething hip-hop heads, and wide-eyed first-timers drank beer out of coffee cups and smoked joint after joint. A kid I knew from queer dance parties showed up, read my astrological chart, and hit on the straight girl in front of us who planned to get a UFO inked on her neck. She was with two doofuses, one of whom announced that he was “just here to meet bitches,” which drew a look from pretty much everyone around him. “Sorry,” he said, but he wasn’t. Later, I felt a twinge of victory when the straight girl ordered him to buy her cigarettes and he was gone, hitting three stores and returning to her with his hands outstretched, like an offering.

My friend showed up late and got in line with someone else, leaving me with no plan and a ragtag group—the straight Queens guys up-talking peyote with blustery bravado while holding an umbrella over my head, the queer kid smoking endless kush out of a vaporizer, and the Christian California couple behind me who went and bought me beer and snacks at 3 a.m. but stared at me, wide-eyed, when the queer kid announced that we were “all gay”—which wasn’t really true, I sleep with women, but whatever, close enough.

“You people might not like this,” the Queens guy just here to hit it with the ladies mumbled to us drunkenly around 4, “but there’s this reggae dance night in the Rockaways you should check out.” Kush Queer smiled politely, while I tried to understand whose people he thought I was exactly—gay ones, I guessed. It occurred to me that, as usual, I straddled the world in which I passed and the one in which I didn’t.

I can always bond, but never commit, to one way of being a man: I belong everywhere and nowhere at once.

Maybe that’s the reality of a lot of my brethren. Younger men aren’t as hampered by social constructions of masculinity, and though we may hunger to reclaim some aspects of it with our boxing clubs and barber shops, we have less of a need to codify what being a man means in primal, no-pain-no-gain terms. Generation Y men do more housework and are more engaged fathers than any generation before. Despite the need to be better feminists, many of us—contrary to what Pharrell thinks—use the term to define ourselves.

I caught sight of my friend after he got a knot tattoo on his arm, and we hugged and then he took off. I’d decided to go my own way with the log cabin, but by 4 I’d lost steam. It had been five hours, someone said the tattooists were drunk, and I felt a little hungover. When the rain kicked up, I told my new friends I was out, collected pounds from all of them, and hopped in a trolling cab.

It was the ride home that, surprisingly, offered me the fraternity I’d spent all night seeking. The driver, a Nigerian man with bad hearing and alarmingly erratic steering, couldn’t find the bridge to get me back to Manhattan. After a few minutes circling the same three blocks, I asked if we were lost. “Yes,” he said, pulling over, actually holding his head in his hands. It was 5 in the morning on a Friday, the salmon sunrise making everything a little sparkly. “I’m so ashamed,” he said.

“It’s all right,” I told him, because it was. He’d turned off the meter, I had nowhere to be, and the rain made the light look magic.

After getting back on the road and asking another cabbie for directions, my man turned around and faced me. “Have you ever been lost?” he asked, his eyes pleading, and I knew that what I wanted was this: a kindness to sand the edge off days filled with tiresome bravado, electric moments of near-violence, shit talk and flexing and avoiding a mysterious fight on Canal with a guy who accused me (wrongly) of “taking pictures of his car.” This moment wasn’t a ritual or a test, but when I answered the cabbie, I felt fraternal.

“I’m always lost,” I said, and we both laughed, two strangers in fragile bodies, connected in our liminal crossing of the bridge, under the sun that just kept on rising over our journey home.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The American Man is a new semi-regular series from Thomas Page McBee that features gonzo reporting from barbers shops, boxing gyms, frat houses, and other bastions of masculinity in an effort to define what makes a modern man.

Thomas Page McBee is the author of the forthcoming book Man Alive: A True Story of Violence, Forgiveness and Becoming a Man. He has written about gender for the New York Times, the Atlantic, Vice, Salon, and the Rumpus, where he pens the column “Self-Made Man.” Follow him on Twitter @thomapagemcbee.