I thought then, and still think, that the film captured a degree of how lost so many Gen X men were in the 1990's (and may still be lost today). However, rather than posing an evolutionary perspective or a new masculinity, it shows men reverting to a more primitive version of masculinity - when you've been emasculated by your culture, you fight and f*ck and stage a revolution against those by whom you feel betrayed.

The solution is not the answer, but it makes for a thought-provoking film. And, by the way, there is also some meditation on the nature of the self in the "relationship" between Tyler and Jack.

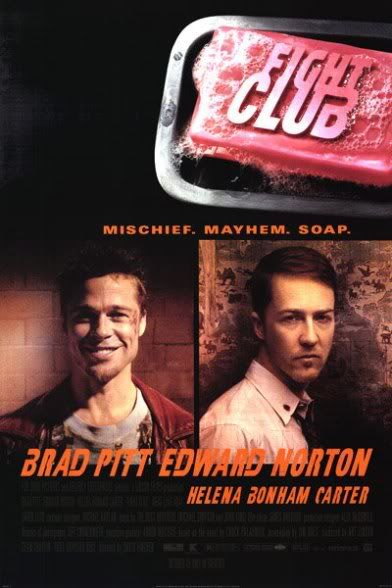

Fight Club Ten Years Later

Kim MorganPosted: November 19, 2009 06:43 PMIf any picture was the movie to usher in the new millennium, it was David Fincher's Fight Club. To me, it was the movie of the 1990s -- as prescient as Network was in the 1970s towards the future of "news," and as equally misunderstood. As Fight Club revealed and essentially, proselytized, we live in a world where we seek to express ourselves, either through conspicuous consumption, or following philosophies for supposed betterment, or to simply remember what it was like to actually feel like a man after the world has feminized us so (something as a woman I find frustrating and heartbreaking -- let men be men again).

But Fight Club isn't saying something as simple and inane as men are pussies. It's not a dumb jock statement of being a "man." Rather, it shows how through the alienation of social institutions, and the de-masculination of culture, the rugged individualist is rare. How to tap into being a man, fast? "Punch me as hard as you can."

Based on the diabolical novel by Portland's Chuck Palahniuk (skillfully adapted by Jim Uhls), Fight Clubis a multifaceted satire. It attacks not only the dehumanizing, corporate Starbucks/Ikea world we inhabit (and still inhabit -- even more), but also self-help philosophies, men's movements, commercials, TV and, interestingly, movies, but oh-so cleverly. The way cinema is blamed for contributing to real-life violence is not only woven into the picture, but it became a reality lobbed at the movie upon release. Like A Clockwork Orange, Fight Club was considered fascist by some critics, that it would encourage men to fight (not always a bad thing), and that it might actually create fight clubs (which it did -- not always a good thing).

A movie that ends on man and woman watching two high rise office towers tumbling down from the skyline before the World Trade Center's collapse is creepy, scary prophetic. As Tyler Durden proclaims: "Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don't need. We're the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives. We've all been raised on television to believe that one day we'd all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars, but we won't. We're slowly learning that fact. And we're very, very pissed off." And...then through the 2000s? A war. And an economic crisis.

Then, to a certain extent, Fight Club took on Generation X, but it also applied to the onset of the next generation. Challenging so many silly articles, books and movies that have attempted to label "Generation X" as listless, flannel-wearing, grunge-listening slackers, the film argued that it's not a lack of passion that kept those in their late twenties to early thirties befuddled, but a lack of personal power, a lack of freedom -- the impotence of not knowing your real soul.

Revealing the absurdity, hilarity and sadness of the type of man who, for example, would sit at home and listen to self-help Guru Anthony Robbins instructing him on how to "awaken the giant within," then go through the motions, and achieving nothing -- Fight Club asks: Do you want to awaken your giant? Do you really want to look inside yourself? What if your giant turns into a monster?

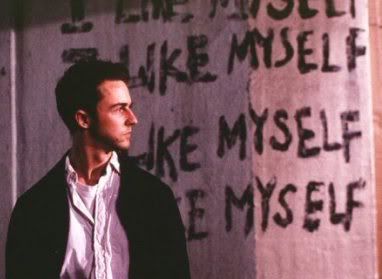

Fight Club begins with a character who is always awake (in fact, he can never sleep) but is certainly no giant --not yet, anyway. The film's insomniac narrator, "Jack" (Edward Norton), like so many of his generation, is full of cynicism but mild-mannered and desperately searching for something -- anything. When he becomes fed up with sleepwalking through his job at a major automobile manufacturer (where, he says, everything looks like "a copy of a copy of a copy"), Jack finally goes to a doctor and begs for sleeping pills. The doctor tells him to quit his whining -- if he really wants to see suffering, he should go to a support group for testicular-cancer survivors. Good idea? Not really for Jack. He soon becomes addicted to every support group he can locate. They become the outlet he's needed for his confounded emotions; he does receive the attention he craves, and he can finally sleep, but he's really just a support group tourist.

His warm fuzzy, self help universe spell is broken when another tourist enters. That's Marla (Helena Bonham Carter), a chain-smoking accidental-overdose-waiting-to-happen who attends meetings because (as she says) "it's cheaper than a movie, and the coffee is free." Jack sees himself reflected in her perverse presence; he hates her, which means he hates himself. They are both fakes.

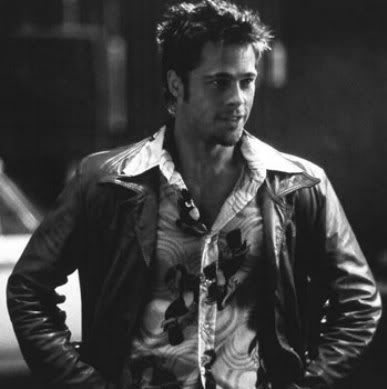

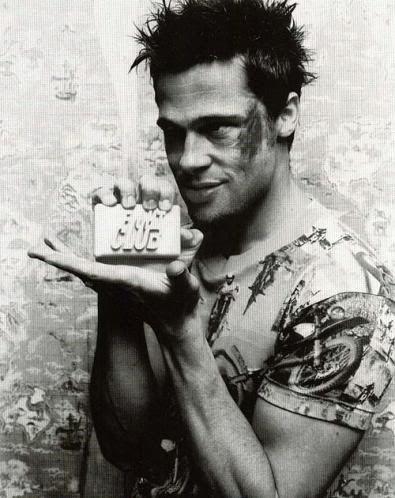

And then the epiphany: During a plane trip, he meets eccentric soap maker Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), he returns home to find his condo has blown up and, desperate, he rushes to, of course, Tyler. He lives in the "dilapidated house in a toxic-waste part of town" -- and never leaves.

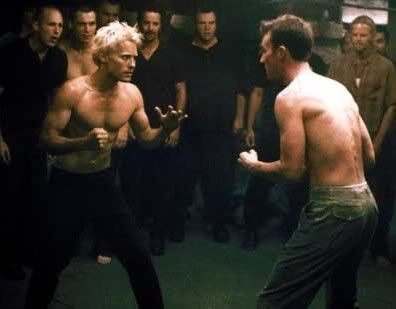

In Tyler, he finally finds the "power animal" that his original cancer-support group instructed him to get in touch with. Tyler teaches him Nietzschean ideals of freedom and puts him in tune with his manly center -- his hunter. And even more importantly, Jack and Tyler fight: Their fights are sweaty, bloody, I want-to-throw-my-desk-at-my-boss releases of rage, submerged eroticism and enlightenment. And men are intrigued. Watching Tyler and Jack's parking-lot brawls creates a new form of therapy for men, and as we well remember, they organize their beat-downs into the movement and philosophy of "Fight Club." As members grow and chapters sprout up in different cities, the club morphs into something called "Project Mayhem" -- a terrorist revolution that encourages members to spread to the outside world -- vigilante/philosophical style with charismatic Tyler as leader of the revolution. In Tyler they trust. His leadership, their trust and their acts become morbidly funny, increasingly frightening and oddly inspiring.

Fincher's brilliant fusion of style and substance created an exciting, thought-provoking, bloody experience that was worshiped, studied and criticized for its controversial takes on moviemaking, manhood, violence and corporate culture. Again, like Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, Fight Club articulates the darkness (and humor) of those who don't want to feel numb anymore while, simultaneously, commenting on the powers that made them numb in the first place. And like Kubrick's film, Fight Club was considered dangerous, a film that incites violence or promotes nihilism.

And this seemed to be exactly what Fincher wanted. The more fingers wagged at him, the more his point was proven: It's easier to pin society's ills on entertainment, then look out into the real world or (gasp) within oneself. (Even if our therapist continues to say: "you're doing great....you're doing great.") Fincher's other masterpiece, Zodiac, also touched on this -- defying what was expected of him, Fincher made a movie about obsession and didn't simply satiate our desire to watch yet another serial killer movie.

But, like all of Fincher's movies, the picture also works as supreme entertainment -- especially because master prankster Tyler is "form of"... Brad Pitt. Does the picture take Tyler's side? In many ways, yes. Though the movie pokes fun at the men who join Tyler, it understands their pain, and it understands that their pain has been sold out to self-help groups that do them no good. In the transformation from "Fight Club" to "Project Mayhem," the members merely shift their anger from each other to the outside world -- the soul-deadening culture that has merged New Age spirituality with consumerism, hiding dehumanization behind politically correct calm. As Tyler explains, "Self-improvement is masturbation...self-destruction might be the answer."

And yet, the picture understands that the answer is too simple; it can only lead to further confusion. Because Fight Club is essentially a satire, it knows that though Tyler's eloquent assertions make sense, and are emboldening, they will become borderline fascistic and not entirely reliable. Still, I couldn't help feeling moved by its muscular assertions. When Tyler declares to a terrified fat cat, whose face has been duct-taped courtesy of Project Mayhem: "We are the people who take out your garbage...we watch over you while you sleep...DO NOT FUCK WITH US!" I'm all Kick-out the-Jams-motherfucker, Fight-the-power exhilarated.

What I admire about Fight Club, is that it never denies that violence can be glamorous. Fincher shows that a fight can be a vital part of life, that a violent act can be horrifying, but weirdly fun and sometimes necessary. It can be a soul-altering experience, it can liberate. But it can also, as the picture artfully complicates by not strictly advocating violence, destroy and entrap one with feelings of paranoia and pain.

Fincher reached new levels in filmmaking, not only by his wink-wink take on violence, but also his wink-wink take on exploiting his own arena of expression: cinema, or rather the corporate world of cinema. Like the pranksters he's chronicling, Fincher had bitten the hand that fed him. He knows the commercial Hollywood system. He knows how to take a successful franchise like Alien, or an ideal hunk like Pitt (something he also deconstructed in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button) and turn it into something subversive, because, as much(or more) than any traditional "indie" director would, he understands the system he mocks. When Tyler yells at his Project Mayhem recruits that they will never be movie stars, the scene works as both a hard truth and as a deconstruction of the movie ideal. Tyler/Pitt is the ideal movie star we all want to be, but should we listen to him?

Yes and no. The film is cynical enough to show that a New World Order like Tyler and Jack's can lose control of itself. Yet the movie doesn't deny that such a "second coming" is attractive and, in ways, beneficial. After all, what is more powerful: movie stars putting knuckles to skin, or fleshy nubs munching scones and itemizing reports? And watching Fight Club, ten years later, with all that we have available to us, it seems even more prescient. For better and often for worse, we've become even more disconnected from ourselves. And even more narcissistic. People text, they twitter, they communicate online instead of talk on the phone or in person. They create alternate identities and pretend to be tough in, of all places, chat rooms, and blogs. Can you imagine a flame war in a biker bar? It's no surprise Fincher's now making a movie about the social networking site Facebook. Tyler Durden would now be a viral creation.

Filled with so many potent comments on society that it demands more than one, two, three viewings, Fight Club is a challenging and powerful work of art that sticks in both the primal and the intellectual parts of one's brain and, for many of us, will never be dislodged -- not even by a sucker punch.

Read more Kim Morgan at her site, Sunset Gun.

No comments:

Post a Comment