Syd Barrett in 1969.

Barrett was officially removed from the band in 1968, and the rumors of his drug use (LSD mostly) and insanity (locked his girlfriend in a cabinet) are widely known and mostly untrue. Yes, he use copious amounts of LSD and other drugs, much of the rest of it is not true.

Also well-known are his struggles with mental illness, which have often been blamed on the drug use, and may well be related to the drugs. What is less well-known is that Barrett was always a little bit of an outsider and that he became more so after the sudden death of his father when he was 16 years old.

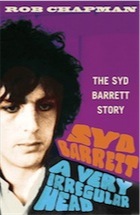

In Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head by Rob Chapman (not available in the US for a while), the life of the musician and the man is told more honestly, it seems in this review, than any of the previous (and many) books about his life.

My guess is that Barrett suffered from mental illness more than excessive drug use, although the drugs more than likely made things worse. His sister denied that he was mentally ill. Here is the Wikipedia section devoted to speculation about his mental state:

There has been much speculation concerning Barrett's psychological well-being. Many believe he suffered from schizophrenia.[14][41][42] A diagnosis of bipolar disorder (aka manic depression) has also been considered.[43]

Barrett's use of psychedelic drugs, especially LSD, during the 1960s is well documented. In an article published in 2006, in response to notions that Barrett's problems were the result of such, Gilmour was quoted as saying: "In my opinion, his nervous breakdown would have happened anyway. It was a deep-rooted thing. But I'll say the psychedelic experience might well have acted as a catalyst. Still, I just don't think he could deal with the vision of success and all the things that went with it."[44]

Many stories of Barrett's erratic behaviour off stage as well as on are also well-documented. In Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey, author Nicholas Schaffner interviewed a number of people who knew Barrett before and during his Pink Floyd days. These included friends Peter and Susan Wynne-Wilson, artist Duggie Fields (with whom Barrett shared a flat during the late 1960s), June Bolan and Storm Thorgerson, among others.

"For June Bolan, the alarm bells began to sound only when Syd kept his girlfriend under lock and key for three days, occasionally shoving a ration of biscuits under the door."[45] A claim of cruelty against Barrett committed by the groupies and hangers-on who frequented his apartment during this period was described by writer and critic Jonathan Meades. "I went [to Barrett's flat] to see Harry and there was this terrible noise. It sounded like heating pipes shaking. I said, 'What's up?' and he sort of giggled and said, 'That's Syd having a bad trip. We put him in the linen cupboard.'"[46] Storm Thorgerson responded to this claim by stating "I do not remember locking Syd up in a cupboard. It sounds to me like pure fantasy, like Jonathan Meades was on dope himself."[46]

Barrett in 1975 during the recording of "Shine On You Crazy Diamond"

In the book Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett and the Dawn of Pink Floyd, authors Mike Watkinson and Pete Anderson included quotes from a story told to them by Thorgerson that underscored how volatile Barrett could be. "On one occasion, I had to pull him off Lynsey (Barrett's girlfriend at the time) because he was beating her over the head with a mandolin."[47]

According to Gilmour in an interview with Nick Kent, the other members of Pink Floyd approached psychiatrist R.D. Laing with the 'Barrett problem'. After hearing a tape of a Barrett conversation, Laing declared him incurable.[48][49]

Gilmour also proposed, in an interview with the National Post's John Geiger, that the stroboscopic lights used in their shows combined with the drugs could have had a seriously detrimental effect on Barrett's mental health if he was a photo-epileptic who suffered partial seizures. When partial seizures occur in the temporal lobes patients are often misdiagnosed with schizophrenia or psychosis.[50]

After Barrett died, his sister, Rosemary Breen, spoke to biographer Tim Willis for The Sunday Times. She insisted that Barrett neither suffered from mental illness nor received treatment for it at any time since they resumed regular contact in the 1980s.[51] She allowed that he did spend some time in a private "home for lost souls" — Greenwoods in Essex — but claimed there was no formal therapy programme there. Some years later, Barrett apparently agreed to sessions with a psychiatrist at Fulbourn psychiatric hospital in Cambridge, but Breen claimed that neither medication nor therapy was considered appropriate in her brother's case.[51]

His sister denied he was a recluse or that he was vague about his past: "Roger may have been a bit selfish — or rather self-absorbed — but when people called him a recluse they were really only projecting their own disappointment. He knew what they wanted, but he wasn't willing to give it to them." Barrett, she said, took up photography, and sometimes they went to the seaside together. "Quite often he took the train on his own to London to look at the major art collections — and he loved flowers. He made regular trips to the Botanic Gardens and to the dahlias at Anglesey Abbey, near Lode. But of course, his passion was his painting", she said.[51][52]

Unfortunately, the people who knew him best - the members of Pink Floyd - refused to be interviewed for this new book.

To lose a father at such an age (as I well know) is to lose the foundation for growing into maturity. In part, this loss may have spurred his creativity, his willingness to push the boundaries, but it also contributed (in my estimation) to his eventual self-destruction. That is the true loss that I think this new book is trying to understand.

Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head by Rob Chapman

Myths grew up about the drugged antics of Pink Floyd's Syd Barrett. The reality was far more poignant, writes Sean O'Hagan

In November 2001, the BBC broadcast Crazy Diamond, a documentary about Syd Barrett, the lost genius of English pastoral psychedelic rock. It featured interviews with members of Pink Floyd, the group that, having jettisoned the troubled guitarist and songwriter in 1968, went on to become one of the biggest acts in the world.

Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head

by Rob Chapman

464pp, Faber and Faber, £12.99

Buy Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head at the Guardian bookshopBarrett went on to become an unsuccessful solo artist and then a recluse, dogged by mental health problems until his death from cancer in 2006. He watched the documentary in his sister Rosemary's house in Cambridge. "He just said, 'It's very noisy. The music's very noisy,'" she tells Rob Chapman, in one of many poignant moments in this fitfully illuminating biography, adding: "He didn't enjoy it. No. Another life, another person."

Barrett's story has often shaded into mythology. Chapman aims to put the record straight. He pinpoints journalist Nick Kent's epic 1974 NME feature, "The Cracked Ballad of Syd Barrett" as the beginning of the myth of Syd. Among the second-hand stories that Kent passed on was the one about Barrett appearing on stage with his hair smeared in Brylcreem and ground-up Mandrax tablets that then melted over his face under the stage lights. That story, like the one about an acid-addled Syd locking his girlfriend in a cupboard and feeding her water biscuits, were both made up but went unquestioned over the years. Both speak of our need to embellish the lives of even the most extreme characters.

Chapman has unravelled the skeins of rumour, exaggeration and anecdote that have been wound so tightly around Barrett. He questions, for instance, the received wisdom concerning the momentum of Barrett's descent into mental turmoil and offers persuasive evidence that his many acts of sabotage with the suddenly famous Pink Floyd in 1967 were designed to derail what he saw as the group's artistic compromise.

In Chapman's words: "Syd was exploring sardonic gestures of defiance." These included his insistence on playing one note constantly during live shows and the recording session in which he introduced a new song called "Have You Got It Yet?", the structure of which he kept changing each time he played it to them.

Nevertheless, the Floyd were driven to distraction by his increasingly disruptive presence and announced his departure in April 1968. They had, in fact, left Syd behind – quite literally – a few months earlier when, on their way to a gig in Southampton, someone took the decision not to pick him up. For a time, he remained unaware of the full extent of their deceit. "It got really embarrassing," Rick Wright, the group's keyboard player and Barrett's then-flatmate, said years later. "I had to say things like, 'Syd, I'm going out to buy a packet of cigarettes' and then go off and play a gig. Of course, he worked out eventually what was going on."

As an example of a peculiar kind of English upper-middle class dynamic in which ruthless ambition is coupled with emotional ineptitude, this, as Chapman points out, takes some beating. But Barrett's betrayal by his bandmates was only one element in a pyschodrama that had much to do with his solitary personality and his fragile sense of self, both of which were assailed by the LSD and downers he took in copious amounts over the preceding year or so.

Barrett carried some heavy adolescent baggage too, though. The product of a solid middle-class family, his youth in Cambridge ended abruptly when his father, Max, died from cancer the week before Barrett's 16th birthday. His friends and associates from the 60s attest to his friendliness and his aloofness, the sense that, even when he was the charismatic centre of things, he was always somehow apart, inside himself. More than one suggests his temperament might have been more suited to painting, his first love, which he returned to briefly but unsuccessfully when he was ejected from Pink Floyd. This, as Chapman says, is one of the many great "what ifs?" of the Syd Barrett story.

Chapman is very good on the array of almost exclusively literary influences that made Barrett such a singular – and definably English – songwriter, citing his debt to Edward Lear, Lewis Carroll, Hilaire Belloc, Kenneth Grahame and even James Joyce, whose strange love poem, "Golden Hair", Syd turned into a kind of narcotic dream-song. Despite Chapman's pleading on his behalf, I suspect that all but the best bits of Barrett's small body of work remain intriguing rather than essential listening.

If Chapman overstates the case for Barrett's songwriting genius and sometimes writes from the point of view of an obsessive on a mission to rehabilitate his hero, A Very Irregular Head is a consistently illuminating, and often surprising, read. Like most things to do with Syd Barrett, though, it inevitably suffers from his absence – and that of Pink Floyd, all of whom declined to be interviewed for the book.

Syd is a looming presence here, an elusive to the point of spectral figure, who haunts the pages of this, the best book yet about him. It sent me back to the music, to songs such as "Dark Globe" with its almost unbearably plaintive final refrain: "Won't you miss me, wouldn't you miss me at all?" In the grain of Syd Barrett's intensely troubled voice, you can hear the darkness descending and his terrible awareness of the same. It is the sound of a man not shining like a diamond, but sinking like a stone.

No comments:

Post a Comment