Here is a little wisdom for the hump-day blahs. Ajahn Sumedho encourages us to be present in the moment, aware of our bodies, our minds, our breathing, our moods - aware of the awareness that it is only Wednesday and there is still much to do and we'd probably rather be doing something else (well, not everyone, some of us are lucky enough to love our jobs).

This is an excerpt from chapter one of his 2010 book, Don’t Take Your Life Personally.

He mentions the great Buddhist teacher, Ajahn Chah, who asked his students to see meditation as a holiday for the heart. So we often we see it as work, something we need to do - but he asked us to see it as something we get to do - a gift, a vacation or holiday.

So when the blahs hit us, whether it's hump-day or Monday, or the kid's diaper needs to be changed - we give our hearts even just a brief holiday by tuning into the body, the breath, our feelings, our thoughts, and simply being present to the moment without judgment, simply holding all that is there with a light touch, with tenderness.

Compose your minds, by Ajahn Sumedho

Posted on 20 April 2011 by Buddhism NowCompose your minds, look inwards and become aware of the here and now ― the body, the breath, the mental state, the mood you are in ― without trying to control or judge or do anything; just allow everything to be what it is.

For many people the attitude towards meditation is one of always trying to change something, always trying to attain a particular state or recreate some kind of blissful experience remembered from the past, or of hoping to reach a certain state by practising. When we practise meditation with the idea of having to do something, however, then even the idea of practice ― even the word ‘meditation’ ― will bring up this idea that ‘if I’m in a bad mood, I should get rid of it’, or ‘if the mind is scattered and I’m all over the place, I should make it one-pointed’. In other words, we make meditation into hard work. So then there is a great deal of failure in it because we try to control everything through these ideas, but that is an impossibility.

Geshe Tashi yesterday was saying that the idea of going off to the cave is very attractive because there you have more control, really. You don’t have to talk to people or get caught up in confusing worldly sensory impingements. As you settle into solitude, you experience a level of tranquillity through lack of sensory stimulation; it is a form of sensory deprivation. That tranquillity, however, is easily disturbed. You can’t sustain it when sensory impingements start pounding away at you again; and then you get into, ‘Let me go to my cave!’ ― that kind of mind; and you begin to hate people. You see them as a threat. ‘Here they come again! They’re going to disrupt my samàdhi (concentration).’ But this cannot possibly be the way to liberation. The other extreme is to think you should not go off to the cave and practise meditation ― ‘Just be natural and let everything happen!’ ― which is true if you can do it that way. But if you don’t even know what is natural yet, it is difficult to trust yourself.

The word ‘meditation’ covers many mental experiences, but the goal of Buddhist meditation is to see things as they are; it is a state of awakened attention. And this is a very simple thing. It isn’t complicated or difficult or something that takes years to achieve. It is so easy, in fact, that you don’t even notice it. When you think in terms of having to practise meditation, you are conceiving it as something you have to attain ― you have to subdue your defilements, you have to control your emotions, you have to develop virtues in order to attain some kind of ideal state of mind. You might have images of a lot of yogis sitting in remote places on mountain tops and in caves. Even a Buddha-image can convey this sense of remoteness and separation if you don’t understand how to use that particular icon; and it all sounds very remote and very far from what you can expect from your life as a human being.

In developing an attitude towards formal practice or daily life practice, therefore, we very often separate the two ― the ‘formal’ and the ‘daily life’. We think of formal practice as a very controlled retreat situation where we all live by a routine, a structure; and when we leave that structured retreat, we refer to ‘daily life meditation’. But that can seem hopeless, can’t it? If we compare daily life with a very controlled meditation retreat, it is very different. But we can’t live in that controlled structure as an ongoing experience. Geshe Tashi made this point last night when he said the real challenge is to develop attention, awakenedness, in the flow of life. This doesn’t remove the option of going on retreat or diminish the value of that in any way. The point is to look at meditation as awakenedness and awareness throughout daily life in whatever way we live and in whatever conditions. There is in that the sense of allowing things to be in this present moment, allowing whatever way the body is or the emotional and mental states right now to be the way they are. Just be the observer of whatever is. Right now the mood is ‘this’, ‘I feel this’. Just be aware whether you are confused, indifferent, happy, sad, uncertain or whatever. Be that which allows things to be what they are.

For the next few minutes try to look inwards with this attitude of observing your mood, your mental quality, your emotional quality. What you find might be very precise like anger, or it might be something that is very sharp. A lot of our emotions are just nebulous, amorphous wandering things, but just put yourself in this position of the Buddha, buddho, the knower, this sense of awakened attention ― not the judge ― but simply looking and noticing what kind of mood or feeling you have right now. When you start noticing, really listening or paying attention and sustaining an awareness on just this mood or this mental state, you become aware of bodily tensions, maybe feelings of bewilderment, or maybe not quite knowing what you are supposed to be doing. But if bewilderment is there, be aware of bewilderment as a mental object. Put yourself in the position of the Buddha, the buddho. Your emotional state and this ‘what am I supposed to be doing?’ will then be seen as a mental object.

Relax into the present. If you try too hard, you put yourself into a state of tension. So it isn’t a matter of making too much effort, but neither is it about not trying at all; it is rather a question of using just the right amount of attention to listen, just enough to be open to this present moment. If you force it, if you try too hard, you don’t relax. Of course, if I say ‘relax!’ that can also mean ‘lax’ and you just fall asleep, so take it to mean just letting go, not having to do anything or get anything.

Awareness or paying attention is not a gaining situation; it is not something to be done in order to get anything or achieve anything; this is not a worldly state that we have to get. We are not being encouraged to get our samàdhi (or concentration as we generally interpret the word), nor is it a matter of proving anything. That generally goes with the fear that we won’t be able to do it. ‘Maybe I’m one of those people that will never get enlightened!’ is another one we all sometimes revert to. ‘I don’t expect to get enlightened in this lifetime; I just don’t have what it takes.’ Well, don’t believe that one, either!

There are all kinds of stress reduction programmes around these days because modern life moves too quickly for us, actually. We are propelled by high technology and all the rest of it into stressful, fast-lane lives whether we like it or not. And this does affect us. We get a sense of being driven and feel restless, and tend to distract ourselves endlessly, which then creates tension and stress. When we do that to the body, however, it creates problems for us. Relaxation is therefore something that is encouraged now in our society, just on a popular, worldly level.

I was listening to a recording recently of a woman teaching relaxation. She said she could not use the word ‘relaxation’ now because people try to relax, so she uses soft, gentle tones of voice instead ‘. . soothing . . . soothing . . .’ This is an expedient method. Words and techniques are meant to help us. They are not like commands or things that we obsess ourselves with. Any kind of meditation technique, or even the language that we use, is not to be taken as a commandment to relax. ‘RELAX!’ in terms of stress reduction would not help very much. What does ‘relaxation’ mean to you? I can’t tell you that, but it is the ability to let go of the obsessive tendencies of feeling we have to do something, it is the ability to let go and let life be. ‘I’ve got to get something I don’t have; I’ve got to get rid of the things that I shouldn’t have!’ These are subconscious influences, as Geshe Tashi was saying last night. They are underlying influences which are so deep that we don’t even notice them. That is why the word ‘relax’ can turn into another thing we have to do. ‘He says I have to relax! I should be able to relax, but I can’t! What’s wrong with me?’ This is where ‘just allowing things to be the way they are’ comes in, simply allowing tension to be. Even if you are stressed out at this moment, let it be the way it is. Let whatever mental states you are in ― even your compulsive tendencies, your obsessive tendencies ― be what they are rather than seeing them as ‘there’s something wrong with me! There’s something I have to get rid of!’ Allow even the bad habits, the bad thoughts, tensions, pain, sadness, loneliness or whatever, to be at this moment; allow the sense of letting go and let life be what it is.

We seem to have problems in the Western world around guilt. This is very much a cultural tendency. In Thailand where I lived for many years, not many people seemed to have this same obsessive feeling. They knew when they had done something they shouldn’t have done; they felt the same sense of shame when they told a lie and so forth, but they didn’t hold to this sense of shame to the point of it becoming a kind of obsession in the way that we seem to. We feel guilty about just breathing the air or being alive, and it can go into neurotic tendencies. This is just my particular reflection on it, anyway. The Dalai Lama said that Tibetans basically like themselves; they have a sense of self-respect. You can see this, actually. One of the things that many of us Westerners find attractive in Asian countries is the fact that people seem somehow happier there; they are more accepting of life and don’t seem to look at things in such a complicated way. I certainly enjoyed living in Thailand. Somehow life there became easier for me, even though in many ways it was more difficult because I was having to learn a new culture and a new language. On an emotional level, however, I found it easier. And Ajahn Chah had an unquestionable acceptance of things as they are and of me as I was. I never felt like that in the United States. I never felt accepted or acceptable as I was; I always felt I should be better. If I were in a good place, I would think, ‘Well, I could be in a better place than this.’ The tendency towards guilt and negativity therefore means that one never feels good enough no matter how hard one tries.

In America you are brought up with this sense of living up to high-minded role models and ideals. You are always looking high up and comparing the realities of what you are with some ideal of what you should be. So you always come off feeling inferior. How can it be otherwise? There is no way out of that one. We are not ideals. This is not an ideal. This is the reality of flesh and blood, nerves and senses; it is all sensitivity. This is not like a Greek statue sculpted in marble and perfect in form. The Greek statue does not have to deal with nerve endings, toothache, old age or anything like that. It is an ideal, an icon like the Buddha-image; it is perfect.

In the case of the Theravadan school, the arahant (fully enlightened one) is the ideal. The tendency there is to take the word ‘arahant’ and place it on a pedestal of idealism so that it remains remote and too high for us. We just cannot relate to it; we merely worship it from down here and maybe feel better for doing so. Looking up and worshipping an ideal can be inspiring ― it can make us feel good ― but then when we come back to ourselves again, to the way we are, what happens in our lives with our families, children, husbands, wives, neighbours, governments?

In community life, like at Amaravati, we are living with basically good people ― and it is a very nice life, a well supported life. Yet the suffering just with the personality conflicts is endless. This person doesn’t get along with that person, and that one doesn’t get along with someone else. But I can’t imagine that it will ever be possible to solve these problems by everyone developing the same personality. Allowing things to be what they are is the attitude I have found most helpful — allowing my own mental states, the way I am on a personal level, my emotional habits, my personality in any of its aspects, good or bad. This also allows me to accept other people for what they are. It is a question of starting from here. If I can’t do it here, I won’t be able to do it with others. Sometimes, how we criticize others is really a reflection of how we look upon ourselves.

Ajahn Chah had this attitude about meditation being a holiday for the heart. We tend to see meditation as something we have to achieve ― another thing we have to do and get ― but Ajahn Chah would put it in the context of a holiday. So try that, try seeing meditation in that way. This is our holiday here, isn’t it? The Summer School is a holiday, but put that word ‘holiday’ also into the context of meditation. You don’t have to achieve anything, get any great insights, attain any high stages, purify yourself, get rid of your evil thoughts, or anything at all. We are not trying to judge thoughts in terms of their quality, for example; we are just noting that they are ‘like this’. If an evil thought comes up ― ‘Go and kill Ajahn Sumedho!’ ― just don’t do it. Refrain from acting. It is just another thought, isn’t it? It is what it is and will go away.

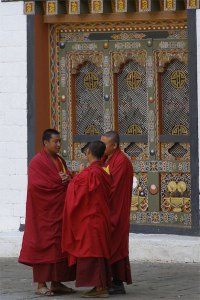

Notice that we like challenges. Some people like to go to extremes, especially younger people. Young monks often want to go to a cave, go on a fast, starve themselves, test themselves by taking on difficult tasks that most people cannot do, because that is part of youth. They make themselves do it. But we can’t do that kind of thing for the whole of our lives; we can’t always be thinking that meditation is some kind of striving challenge for us. The real challenge actually lies in just being able to integrate awareness into the most ordinary things, into the mundane realities of daily life, into the most unimpressive aspects of what we do every day. This is being aware as a continuum. Being aware of special situations is one thing, but to have a connected awareness ― the continuum of awareness ― is not so easy; it does take patience. When you grasp the idea of continuous awareness, you want to do it, but the realities are that you get distracted and easily fall back into old habits, so patience is required.

One suggestion of how to maintain awareness, is to have a sense of humility and simplicity. These things help. There is a monk at Amaravati who tends to strive too hard, then fail, then get depressed, then frustrated by the thought that he needs more solitude, more isolation and a different environment. He thinks there are too many distractions at Amaravati, too many people. One way I have of handling this is to be grateful for the moments I am mindful. If I get caught up in the life of the monastery, pulled this way and that and am not very mindful, then suddenly ― I remember! And I treasure that; I value that rather than think, ‘Oh, I’m trying to be mindful but I can’t do it,’ and beating myself up because I vowed in the morning to be mindful the whole day, but failed. I would go into these states of, ‘Oh, there I go again; I shouldn’t have done that!’ and nag myself, criticize myself and feel like a failure. But even if there is only one moment in the whole day when I am mindful, I can feel this ‘thank you!’ To me that is more helpful than beating yourself up, because that doesn’t help you in any way. Meditation is not a matter of success, of being able to achieve goals and prove ourselves. Remember that.

Our emotional habits are often built around success and failure ― elated by success and depressed by failure. The way to transcend that, however, is through awareness just in this present moment, this simple act of attention, this listening, openness and receptivity. Then there is a sense of relief ― such a relief!

~ Extract from - Don’t Take Your Life Personally.

By Ajahn Sumedho

Chapter One, Starting from Here

© Buddhist Publishing Group

No comments:

Post a Comment