I used to be into cycling when I was young (now I am just a spectator, aside from work on my spinner), inspired by Greg LeMond and the very minimal coverage that professional cycling received in the U.S.

But I was also inspired by the U.S. speed-skater Eric Heiden who turned to road cycling after he gave up speed skating.

After winning gold in all five long track speed skating events (a feat no one else has ever done, or likely ever will) at Lake Placid in 1980 (as a 21-year-old), Heiden abruptly switched to cycling. He easily could have competed in another Olympics and cemented his position as a legend in the sport.

Instead he went to on to win the 1985 U.S. National Championship road race, finish the 1985 Giro d’Italia, and crash out of the 1986 Tour de France five days before the finish. After he quit cycling, he went back to school and became a doctor, and is now a well-known orthopedic surgeon.

This is why Heiden is a man I admire - he was a world-class athlete but he is also intelligent and motivated to be great at whatever he does.

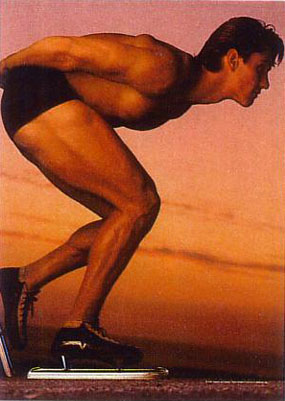

And . . . Heiden had massive legs:

It turns out that his legs are small in comparison to some of the track cyclists, guys who don't have to worry about endurance or keeping their weight down to get over the big mountains in a road race.

One of the most interesting pictures to come from this year's Olympics, which has become the basis for an article in the New York Times, features German road cycling sprint legend Andre Greipel (the Gorilla) having a "quad off" with track cyclist Robert Förstemann (Mr. Thigh). It looks unreal:

Greipel is on the left. Förstemann has thighs that measure 34 inches - his waist is smaller than that.

The amount of training and effort it would take to have thighs that large is mind-boggling. I have no doubt there are a lot of bodybuilders with thighs that size, but they use drugs (a lot of drugs) and the legs are generally in proportion tot he rest of their bodies, unlike these track cyclists who look just a little freakish.

Here is some of the New York Times article:

“The picture is definitely real,” said Benjamin Sharp, the high-performance endurance director for USA Cycling. “Cyclists have strange shapes: big quads, small waists and big butts. It’s hard to find pants.”He paused, then added, “It’s funny we’re talking about this.”Olympic track cycling started Thursday, inside the velodrome, where seemingly everything, including the design of the arena, the track inside and the athletes’ helmets, emphasized the sleek and the slim. Everything, that is, except the thick, bulky and somewhat frightening quadriceps of the competitors.To cycling teams and their support staffs, this is less an Olympic oddity and more a necessity specific to their sport. The British track cyclist Chris Hoy, who collected his fifth career gold medal in the men’s team sprint Thursday, noted recently that his thighs measured 27 inches, or size 8 for a woman’s waist. Of course, Hoy can also cover a kilometer on his bicycle in under a minute.Hoy’s former teammate Jamie Staff could fit his wife’s skirt snug around one thigh when he won a gold medal at the Beijing Games.“Insane,” said Staff, now a USA Cycling coach. “Basically, going quick on a bike as a sprinter is about leg speed and leg strength. Naturally, quads help.”Beth Newell, a United States national champion from California, is considered something of an international quad expert in cycling circles. She first measured the muscle when a skinny friend suggested that Newell’s quads were bigger than the friend’s head.In a 2007 blog post Newell outlined the steps for proper quadriceps measurement. One: wrap string around the thickest part of the leg. Two: align string with tape measure. Three: pull string taut. From then on, Newell became, in her own words, “a crusader to glorify the big quad,” updating her Web site with her latest measurements and those of her competitors.Improper measurement drove Newell bonkers. Unlike their track counterparts, road cyclists, as endurance riders, often balk at the reality of their thigh size, she said, when they should celebrate it instead. Her advice: Go for girth.“It isn’t like measuring waistlines for skinny minnies,” Newell wrote in an e-mail. “This is about bragging about massive (sometimes) muscular quads! The people making those comments obviously didn’t get the point. Go big or go home!”Athletes tabbed the baseline measurement for an acceptable sprint cyclist’s thigh at 60 centimeters, or 23.6 inches. Newell cited the American cyclist Jennie Reed as someone she envied in that regard.Hoy noted in recent interviews that some of his competitors’ thighs made his look skinny. Perhaps there was a bit of thigh envy involved. Regardless, no one disputes that the biggest thighs in cycling belong to Förstemann, whom Newell referred to as Quadzilla.“Those German track sprinters are pretty much legendary,” she wrote. “I don’t think any of them have names, even. They just get referred to by their quad size.“Herr Achtzig to the line,” Newell wrote, using the German for Mr. Eighty.To be fair, participants did note that quad size does not necessarily correlate to speed. Imagine a sumo wrestler, for instance, on a race bike. Victoria Pendleton of Britain, winner of nine world titles and of a gold medal on Thursday, is but one example of the regular-size-thigh cycling set.Lack of quad size, though, can doom even the most promising young riders, the equivalent of a weight lifter with small biceps. Big thighs, the participants said, serve as an intimidation factor before races, a way to send a message to competitors without speaking, with no more than a quick flex.Newell said some riders rubbed warming oil on their quadriceps before races, because the shine accentuates the size of the muscles, giving them that bodybuilder cut. She argued against team uniforms that included thinning stripes, a “serious no-no” in the quad game.“I mean, we pedal hours and hours every week — it’s a full-time job — so often, our bodies are seen as a measurement of our ability,” she wrote.Much of a cyclist’s thigh growth, Sharp said, is natural, the byproduct even of particular positions on the bike. Sprinters who sit hunched over, more compact, tend to use their quadriceps more, and because they spend thousands of hours in the same position, the body conforms accordingly.Staff said much of his thigh expansion came from workouts. He loved that part of cycling, in particular the squats. His exploits in that lift still live in videos on YouTube. At his peak, Staff said, he could squat about 529 pounds.Even now, when he is retired and coaching, his thighs compare favorably to those of the athletes on his team. He could still win a quad-off, which is cycling’s version of the male model walk-off in the movie “Zoolander.”

No comments:

Post a Comment