This morning, Tricycle's Daily Dharma quote was from Pema Chodron, a short piece taken from an excerpted section of The Places that Scare You: A Guide to Fearlessness in Difficult Times (2001). In this short section she also addresses the idea of the spiritual warrior, which is fitting since she was Trungpa's student up until his death.

I think these are important first steps in reframing the warrior archetype toward a more compassionate and self-aware ideal. One of the things I like about Trugpa's vision of the spiritual warrior is his emphasis on having a "warrior heart."

Warriorship is so tender, without skin, without tissue, naked and raw. It is soft and gentle. You have renounced putting on a new suit of armor. You have renounced growing a thick, hard skin. You are willing to expose naked flesh, bone, and marrow to the world.

~ Adapted from Smile at Fear: Awakening the True Heart of Bravery, by Chogyam Trungpa. Copyright 2009 by Diana J, Mukpo.Jayson's post first:

The Modern Day Spiritual Warrior

January 5, 2013

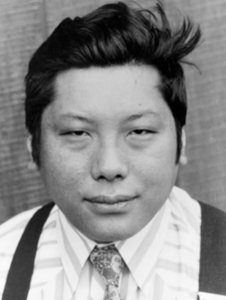

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Recently, I realized that I’m in the business of training warriors.

But what is a warrior? what exactly do I mean?

I have not been able to find a better term than warrior. Sure, there is Jedi, Samurai, badass, etc.

But warrior is the closest term I have found for what I’m attempting to describe. And, I love that one of my teachers Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche spoke of the sacred warrior. He was speaking to the spiritual practitioner who is willing to face their life head on and help others eliminate their suffering. It’s a bold path.

So, the term warrior must be defined here. I get that “warrior” conjures up a lot of historycially and traditional masculine roles. Pick any movie from Gladiator, to Braveheart, to Hunger Games. They all have a hero or heroine who fights to save their people or save the day. But I am not so idealistic or naive here. Sure, we are all great, heros and heroines in our own right. But let’s be realistic and true, meeting our lives directly free from unrealistic expectations, magical thinking, or fairy tales.

So, here’s my definition (or better yet aspiration) of the modern day spiritual warrior:

A modern day spiritual warrior is first and foremost a student of his or her own, direct experience. She is committed to being herself completely and her life journey is about coming home to who she really is. He is always learning, always growing. Her courage gives her the power and choice to face “what is so” directly and head on. He turns toward the darkness in order to transmute it. She learns to train the mind to serve the heart. He learns to “hold his seat” in the midst of life’s challenges. He learns to own and tame his inner stallion so that he may ride him powerfully and elegantly. She is willing to fall down, fail miserably, and get back up in order to be herself. He is embodied, emotionally literate, relationally adept. She is willing to fight, even die, for truth, love, and family. He enjoys the practice of burning up in this way. She desires, and is willing, to go all the way.And, for the men out there, here’s a quick video about an upcoming warrior training.

And here is the Pema Chodron excerpt:

The In-between State

Pema Chodron points to the perfect training ground for the spiritual warrior—anxiety, heartbreak, and tenderness.

By Pema Chodron

The secret of Zen is just two words: not always so.—Shunryu Suzuki RoshiIt takes some training to equate complete letting go with comfort. But in fact, "nothing to hold on to" is the root of happiness. There's a sense of freedom when we accept that we're not in control. Pointing ourselves toward what we would most like to avoid makes our barriers and shields permeable.This may lead to a don't-know-what-to-do kind of feeling, a sense of being caught in-between. On the one hand, we're completely fed up with seeking comfort from what we can eat, drink, smoke, or couple with. We're also fed up with beliefs, ideas, and "isms" of all kinds. But on the other hand, we wish it were true that outer comfort could bring lasting happiness.

This in-between state is where the warrior spends a lot of time growing up. We'd give anything to have the comfort we used to get from eating a pizza or watching a video. However, even though those things can be pleasurable, we've seen that eating a pizza or watching a video is a feeble match for our suffering. We notice this especially when things are falling apart. If we've just learned that we have cancer, eating a pizza doesn't do much to cheer us up. If someone we love has just died or walked out, the outer places we go to for comfort feel feeble and ephemeral.

We are told about the pain of chasing after pleasure and the futility of running from pain. We hear also about the joy of awakening, of realizing our interconnectedness, of trusting the openness of our hearts and minds. But we aren't told all that much about this state of being in-between, no longer able to get our old comfort from the our side but not yet dwelling in a continual sense of equanimity and warmth.

Anxiety, heartbreak, and tenderness mark the in-between state. It's the kind of place we usually want to avoid. The challenge is to stay in the middle rather than buy into struggle and complaint. The challenge is to let it soften us rather than make us more rigid and afraid. Becoming intimate with the queasy feeling of being in the middle of nowhere only makes our hearts more tender. When we are brave enough to stay in the middle, compassion arises spontaneously. By not knowing, not hoping to know, and not acting like we know what's happening, we begin to access our inner strength.

Yet it seems reasonable to want some kind of relief. If we can make the situation right or wrong, if we can pin it down in any way, then we are on familiar ground. But something has shaken up our habitual patterns and frequently they no longer work. Staying with volatile energy gradually becomes more comfortable than acting it out or repressing it. This open-ended tender place is called bodhichitta. Staying with it is what heals. It allows us to let go of our self-importance. It's how the warrior learns to love.

This is exactly how we're training every time we sit in meditation. We see what comes up, acknowledge that with kindness, and let go. Thoughts and emotions rise and fall. Some are more convincing than. others. Habitually we are so uncomfortable with that churned-up feeling that we'd do anything to make it go away. Instead we kindly encourage ourselves to stay with our agitated energy by returning to the breath. This is the basic training in maitri that we need to just keep going forward, to just keep opening our heart.

Dwelling in the in-between state requires learning to contain the paradox of something's being both right and wrong, of someone's being strong and loving and also angry, uptight, and stingy. In that painful moment when we don't live up to our own standards, do we condemn ourselves or truly appreciate the paradox of being human? Can we forgive ourselves and stay in touch with our good and tender heart? When someone pushes our buttons, do we set our to make the person wrong? Or do we repress our reaction with "I'm supposed to be loving. How could I hold this negative thought?" Our practice is to stay with the uneasiness and not solidify into a view. We can meditate, do tonglen, or simply look at the open sky—anything that encourages us to stay on the brink and not solidify into a view.

When we find ourselves in a place of discomfort and fear, when we're in a dispute, when the doctor says we need tests to see what's wrong, we'll find that we want to blame, to take sides, to stand our ground. We feel we must have some resolution. We want to hold our familiar view. For the warrior, "right" is as extreme a view as "wrong." They both block our innate wisdom. When we stand at the crossroads, not knowing which way to go, we abide in prajnaparamita. The crossroads is an important place in the training of a warrior. It's where our solid views begin to dissolve.

Holding the paradox is not something any of us will suddenly be able to do. That's why we're encouraged to spend our whole lives training with uncertainty, ambiguity, insecurity. To stay in the middle prepares us to meet the unknown without fear; it prepares us to face both our life and our death. The in-between state—where moment by moment the warrior finds himself learning to let go—is the perfect training ground. It really doesn't matter if we feel depressed about that or inspired. There is absolutely no way to do this just right. That's why compassion and maitri, along with courage, are vital: they give us the resources to be genuine about where we are, but at the same time to know that we are always in transition, that the only time is now, and that the future is completely unpredictable and open.

As we continue to train, we evolve beyond the little me who continually seeks zones of comfort. We gradually discover that we are big enough to hold something that is neither lie nor truth, neither pure nor impure, neither bad nor good. But first we have to appreciate the richness of the groundless state and hang in there.

It's important to hear about this in-between state. Otherwise we think the warrior's journey is one way or the other; either we're all caught up or we're free. The fact is that we spend a long time in the middle. This juicy spot is a fruitful place to be. Resting here completely—steadfastly experiencing the clarity of the present moment—is called enlightenment. ▼

Pema Chodron, an American Buddhist nun, is a founding member and resident teacher at Gampo Abbey, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, the first Tibetan Buddhist monastery in North America established for Westerners. Excerpted from The Places That Scare You © 2001 by Pema Chodron.

No comments:

Post a Comment