It's sad that we have lost the freedom to be close to each other both physically and emotionally because we are afraid to be called "gay" or "fag."

This is a good reminder that with all the progress we have made as a species in some realms, in other realms we have lost valuable traits and freedoms.

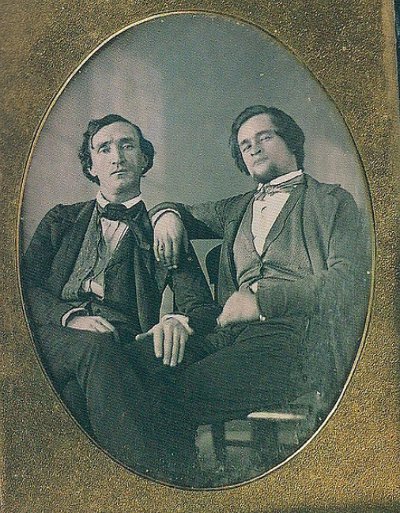

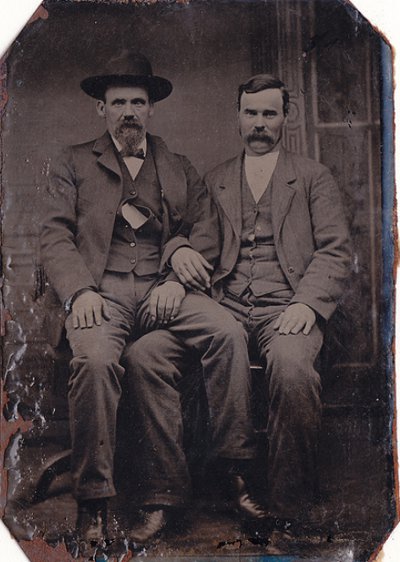

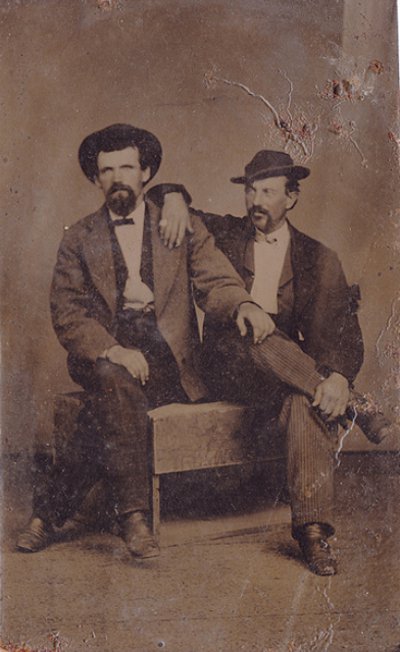

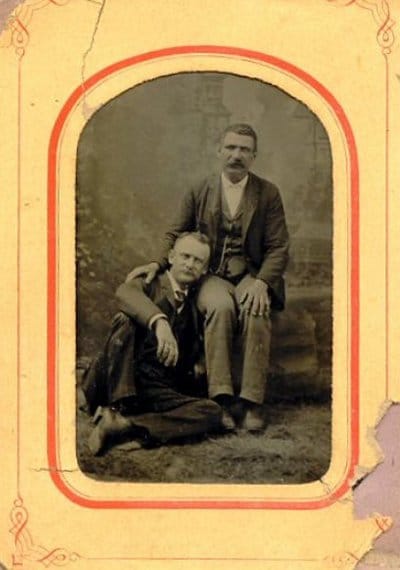

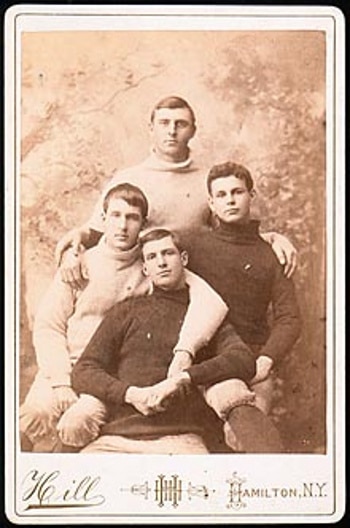

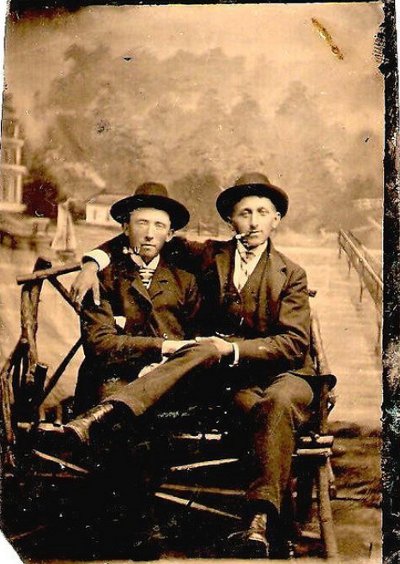

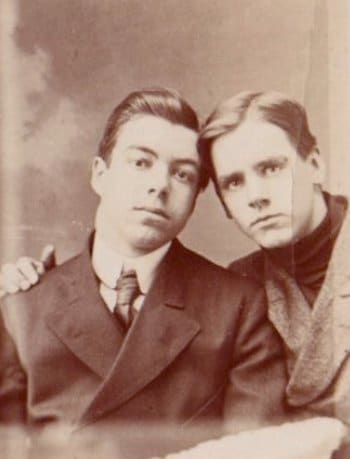

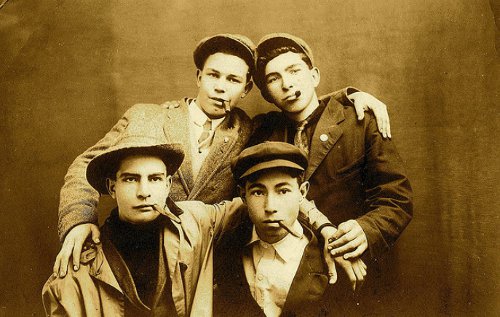

Bosom Buddies: A Photo History of Male Affection

Brett and Kate McKay

July 29, 2012

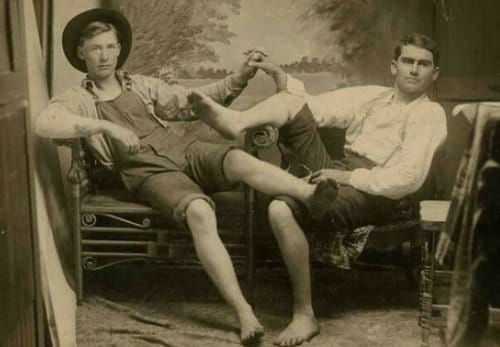

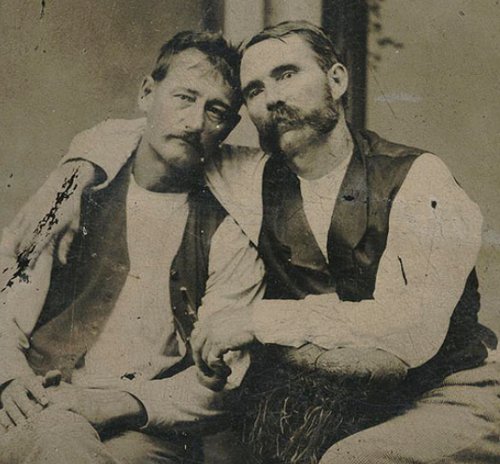

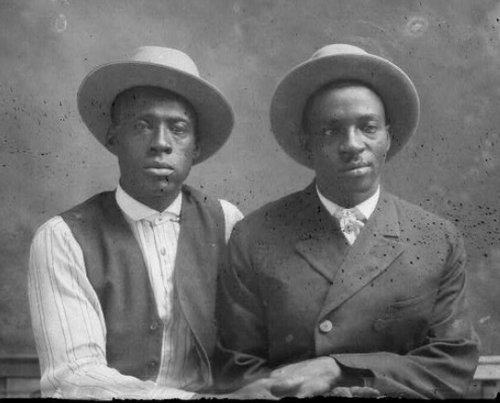

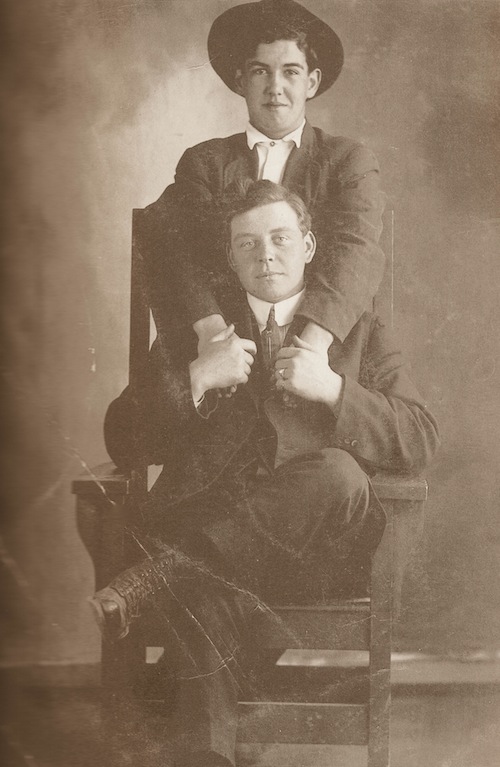

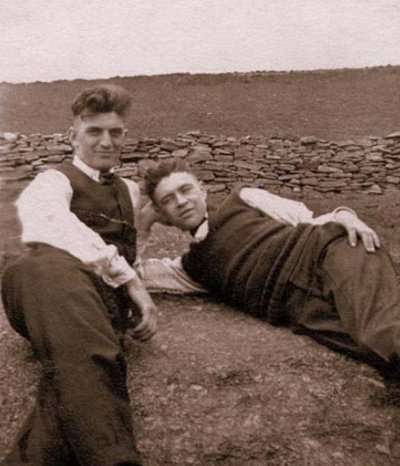

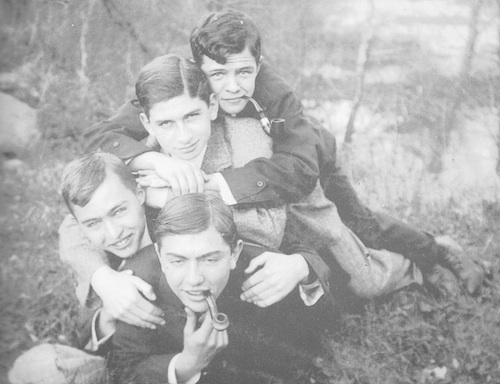

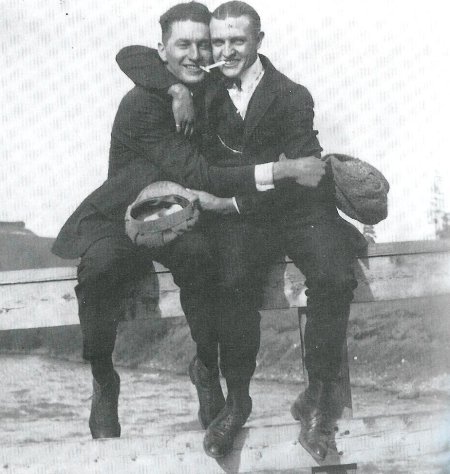

In my unending search for just the right vintage images for our articles, I have looked through thousands of photographs of men from the last century or so. One of the things that I have found most fascinating about many of these images, is the ease, familiarity, and intimacy, which men used to exhibit in photographs with their friends and compadres.

I shared a handful of these images in our very early post on the history of male friendship, but today I wanted to share almost 100 more in order to provide a more in-depth look into an important and highly interesting aspect of masculine history: the decline of male intimacy over the last century.

As you make your way through the photos below, many of you will undoubtedly feel a keen sense of surprise — some of you may even recoil a bit as you think, “Holy smokes! That’s so gay!”

The poses, facial expressions, and body language of the men below will strike the modern viewer as very gay indeed. But it is crucial to understand that you cannot view these photographs through the prism of our modern culture and current conception of homosexuality. The term “homosexuality” was in fact not coined until 1869, and before that time, the strict dichotomy between “gay” and “straight” did not yet exist. Attraction to, and sexual activity with other men was thought of as something you did, not something you were. It was a behavior — accepted by some cultures and considered sinful by others.

But at the turn of the 20th century, the idea of homosexuality shifted from a practice to a lifestyle and an identity. You did not have temptations towards a certain sin, you were a homosexual person. Thinking of men as either “homosexual” or “heterosexual” became common. And this new category of identity was at the same time pathologized — decried by psychiatrists as a mental illness, by ministers as a perversion, and by politicians as something to be legislated against. As this new conception of homosexuality as a stigmatized and onerous identifier took root in American culture, men began to be much more careful to not send messages to other men, and to women, that they were gay. And this is the reason why, it is theorized, men have become less comfortable with showing affection towards each other over the last century. At the same time, it also may explain why in countries with a more conservative, religious culture, such as in Africa or the Middle East, where men do engage in homosexual acts, but still consider homosexuality the “crime that cannot be spoken,” it remains common for men to be affectionate with one another and comfortable with things like holding hands as they walk.

Whether the men below were gay in the way our current culture understands that idea, or in the way that they themselves understood it, is unknowable. What we do know is that the men would not have thought their poses and body language had anything at all to do with that question. What you see in the photographs was common, not rare; the photos are not about sexuality, but intimacy.

These photos showcase an evolution in the way men relate to one another — and the way in which certain forms and expressions of male intimacy have disappeared over the last century.

It has been said that a picture tells a thousand words, so while I have provided a little commentary below, I invite you to interpret the photos yourselves, and to ask and discuss questions such as: “Who were these men?” “What was the nature of their relationships?” “Why has male intimacy decreased and what are the repercussions for the emotional lives of men today?”

Men as Friends

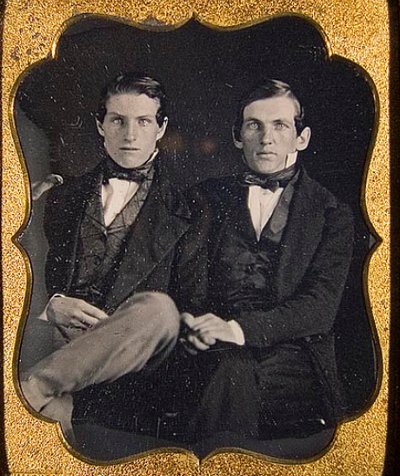

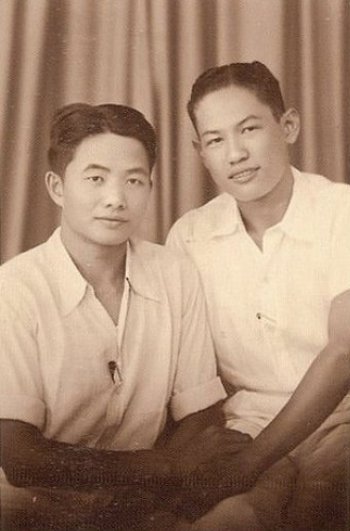

Portraits

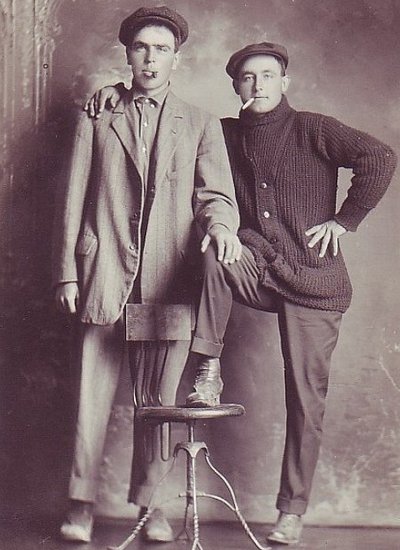

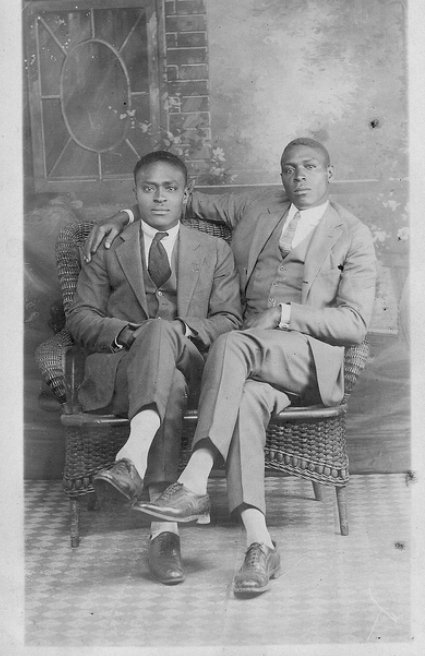

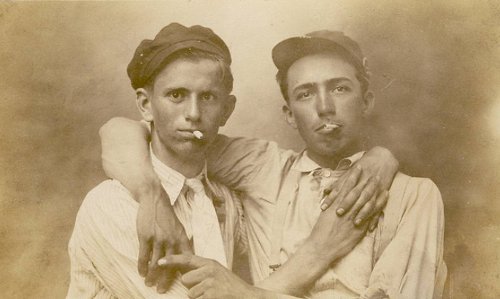

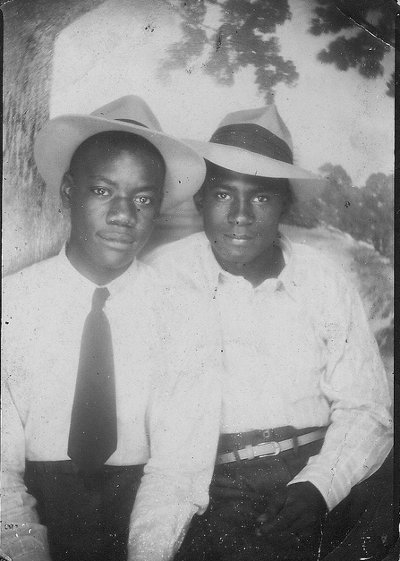

From the Civil War through the 1920′s, it was very common for male friends to visit a photographer’s studio together to have a portrait done as a memento of their love and loyalty. Photographers would offer various backgrounds and props the men could choose from to use in the picture. Sometimes the men would act out scenes; sometimes they’d simply sit side-by-side; sometimes they’d sit on each other’s laps or hold hands. The men’s very comfortable and familiar poses and body language might make the men look like gay lovers to the modern eye — and they could very well have been — but that was not the message they were sending at the time. The photographer’s studio would have been at the center of town, well-known by everyone, and one’s neighbors would having been sitting in the waiting room just a few feet away. Because homosexuality, even if thought of as a practice rather than an identity, was not something publicly expressed, these men were not knowingly outing themselves in these shots; their poses were common, and simply reflected the intimacy and intensity of male friendships at the time — none of these photos would have caused their contemporaries to bat an eye.

When the author of Picturing Men, John Ibson, conducted a survey of modern day portrait studios to ask if they had ever had two men come in to have their photo taken, he found that the event was so rare that many of the photographers he spoke to had never seen it happen during their career.

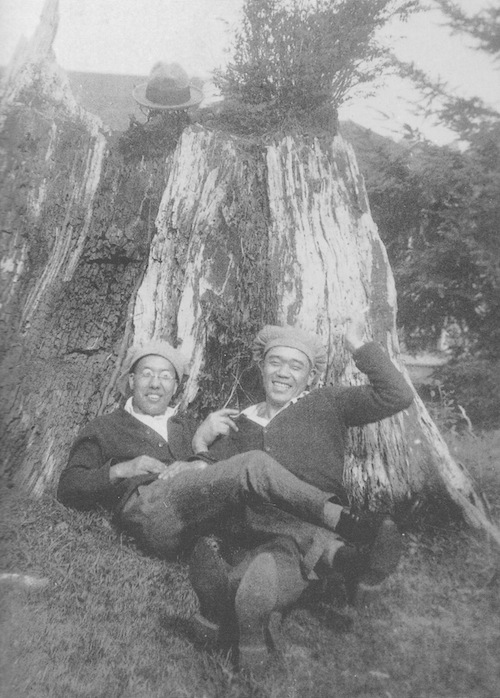

Snapshots

When portable cameras for the amateur photographer became more widely available, they allowed men to photograph themselves in a greater range of more spontaneous situations, and the practice of sitting for formal portraits together waned in the 1930s. The snapshots usually were developed by someone else who would have gotten a look at all of them, so again, these pictures were not likely purposeful expressions of gay love, but rather captured the very common level of comfort men felt with one another during the early 20th century.

One of the reasons male friendships were so intense during the 19th and early 20th centuries, is that socialization was largely separated by sex; men spent most their time with other men, women with other women. In the 50s, some psychologists theorized that gender-segregated socialization spurred homosexuality, and as cultural mores changed in general, snapshots of only men together were supplanted by those of coed groups.

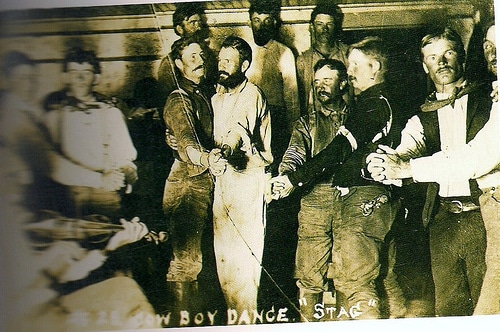

In all male environments, such as mining camps or navy ships, it was common for men to hold dances, with half the men wearing a patch or some other marker to designate them as the “women” for the evening.

Forming pyramids on the beach was a popular pastime for men through the 30s.

There's more at The Art of Manliness.

No comments:

Post a Comment