However, it also makes some stereotypical assumptions about men who have opted out of traditional masculinity. I'm willing to grant that the four types Grose identifies probably exist. There are others of us who have opted out of those stale gender roles and are not these "losers," nor are we alpha males.

We are individuated men - secure in our masculinity - who have rejected dominance as a valid part of manhood, and who are also able to express compassion and emotions, able to be soft without being mushy. We are whole.

Omega Males and the Women Who Hate Them

They're unemployed, romantically challenged, and they're everywhere.

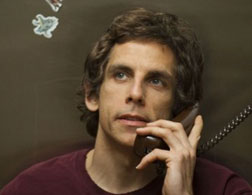

In the Noah Baumbach movie Greenberg, out in limited release this Friday, the eponymous main character is having trouble being a man. The 41-year-old Greenberg, played by Ben Stiller, tells his 25-year-old love interest that when he was a kid he dreamed of being an astronaut. Now he can't even drive, much less pilot a shuttle. He sabotaged his career as a musician, so he's trying the old-fashioned, manly pursuit of carpentry. He pretends not to care about his new line of work—he tells his friends he's doing "nothing for a while"—yet Greenberg is seriously wounded when an ex-girlfriend tells him she doesn't remember the bed he built for her. All she recalls are his anxiety attacks.Greenberg is pretty much the fictional representation of the masculinity crisis that Susan Faludi outlined in her 1999 book Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man. Men like Greenberg, Faludi argued, were led to believe as boys that they were "going to be the master of the universe and all that was in it," that they'd be astronauts conquering the final space frontier or, at the very least, that they would master a lifelong stable job and a healthy family. But by the '90s, Greenberg types found themselves "masters of nothing." The latest recession is only making it more so, as job security becomes a fantasy for many, and marriage rates plummet.

And yet men are still tragically unable to retool. The image of the American woman has gone through several upheavals since the 1950s, but the masculine ideal seems fixed in cultural aspic: Think slick ad executive Don Draper in Mad Men and the WWII heroes in the Tom Hanks-produced HBO series The Pacific. So his confused, paralyzed counterpart is cropping up in ever-more variations on TV and in movies: the omega male.In the social hierarchy of a wolf pack in captivity, the omega ranks below the alpha and beta wolves. In human terms, if an executive or a warrior is an alpha male and a nice-guy middle manager like The Office's Jim Halpert is a beta male, then Greenberg and his brethren are omega males. While the alpha male wants to dominate and the beta male just wants to get by, the omega male has either opted out or, if he used to try, given up. Greenberg says of his somewhat stunted best friend, "We call each other 'man,' but it's a joke. It's like imitating other people." The omega male is not experiencing the tired trope of the midlife crisis. A midlife crisis implies agency, a man who has the job and the family and chooses to reject it. The omega male doesn't have the power to reject anything—he's the one who has been brushed off. He's generally unemployed, and his romantic relationships are in shambles—he's either single or, if he's married, not happy about it. "I'm doing nothing and I'm tied to no one," Greenberg boasts.

As a seemingly educated guy who travels in culturally elite circles, Greenberg is just one variety of omega male. Here's a taxonomy of the different types you might find skulking across the small and large screens.

The Liberal Arts Layabout: Since he's hanging out with successful artist types, Greenberg falls into this category, along with other Noah Baumbach characters (Jack Black in Margot at the Wedding, Chris Eigeman in Kicking and Screaming) and every role that Jason Schwartzman has ever played. They are usually failed artists of some sort, often surrounded by more successful friends and relatives. The bitter ones—Greenberg, Chris Eigeman—hide their inability to live up to the demands of the world with cynicism verging on cruelty. For example, after yelling, unprovoked, at his young lover Florence, Greenberg tells her that it's partially her fault and that she should "take some responsibility for trying to see me." The sweeter ones—Jason Schwartzman in Bored to Death—retreat to an elaborate fantasy world. In Bored to Death, Schwartzman plays Jonathan Ames, a writer whose career has stalled. He decides to become an amateur private eye after reading too many pulp novels and is mostly incompetent at his new fake job.

The Mimbo: Unlike the liberal arts layabout, the mimbo revels in not participating in mainstream masculine culture. This character is very good-looking (hence the contraction—male bimbo) but doesn't necessarily use his looks for personal gain. Mimbos of TV and film include Cougar Town's Brian Van Holt, who plays the lead character's hapless, underemployed golf-pro ex-husband, and Dax Shepard's vain "male model" in When in Rome. Though Shepard's character is obsessed with his own "shredded" physique, he can't make it translate into gainful employment or public adulation: The photos in his modeling book were all done on spec, and when he takes his shirt off in a cafe, everyone hectors him to put it back on. Despite his lack of steady employment or fulfilling relationships, Van Holt's Cougar Town character, Bobby Cobb, is so secure in his alternative masculinity that in a recent episode he was not even embarrassed when he was beaten up and robbed by a woman.

Beer Guy: As Kerry Howley pointed out in an XX Factor post from earlier this year, beer guy appeared in many of the sexist ads that ran during the Super Bowl. There are two variations on this type: original beer guy and sad beer guy. Original beer guy is a mimbo gone to seed. He's a happy couch potato, crashing a book club with his buddies from the softball league just to score some Bud Light. He is unbothered by his inability to live up to the masculine ideal—unlike sad beer guy, who is hyperaware of the fact that he is falling short. The middle-aged dudes on Men of a Certain Age—an unemployed actor, a man whose marriage fell apart because of his gambling addiction, and an unhappy car salesman—are sad beer guys. So are the miserable-looking men in the infamous Dodge Charger Super Bowl ad who appeared to be crushed by the responsibilities of their days, which didn't just include working long hours but also dealing with the demands of their wives. As a New Jersey Star-Ledger review of Men of a Certain Age says of Ray Romano's character in that show, "Joe is a man who misses his wife, cares about his kids, depends on his friends but also feels like he should be doing better with all of them, if he could only figure out how."

The Game Boy: The Apatovian stoners and the passive lads of Grandma's Boy (whom Reihan Salam termed beta males in this Slate article from 2006) are exemplary game boys. These men live in a perpetually adolescent zone, ignoring adult responsibilities unless they are forced to consider them. If they're employed, it's playing video games (Grandma's Boy) or creating a redundant Web site listing movie nude scenes (as in the Apatow flick Knocked Up). The newest entry in the game-boy posse is the star of She's Out of My League, Apatow crony Jay Baruchel. In that movie, Baruchel plays a nebbishy TSA airport screener who somehow nabs a blond, hot event-planner with a law degree. Though Baruchel may get the girl at the end of the film, as EW reviewer Owen Gleiberman writes, "He's a socially inept underachiever who works in airport security, and she's a high-end event planner who oozes poise and would never be drawn to such a gawky, shambling loser." Sounds like the writers are stuck in the same game-boy male dream-world that their characters inhabit.

1 comment:

Problem: comedy isn't cultural prescription. If anything, it's the opposite. If we're laughing at the dumb TV dad or the loser layabout, the implicit message is "you can laugh at this type because you're not like this type." I laugh at Homer Simpson or the guy in a Super Bowl ad, not because I long to be like him, but because I feel superior to him. Comedy usually flatters the viewer's sense of superiority; it doesn't *endorse* the types it shows.

It's a complicated affair trying to back-construct what the moralizing ideal is when you're being encouraged to laugh at a type. The ideal is hidden, implicit, not stated directly.

A lot of crappy cultural critique goes off on wild, adamant goose chases because it doesn't think this through carefully.

Post a Comment