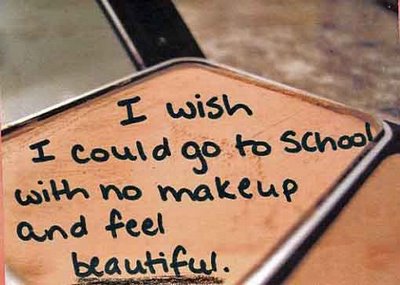

Our culture has objectified women for a very long time - and many men still do this. However, objectification does exactly what that word implies: it makes a fully human, multi-dimensional human being into an object, an inanimate, one-dimensional plaything.

We know that objectification hurts a woman's self-esteem and self-image. Now we know that it also impairs their cognitive ability (as a result of dividing cognitive energy between two self-images). Key point about objectification:

A woman in this situation simultaneously sees herself as a unique individual and a generic sexual being. Dividing the psyche in this uncomfortable way “is likely to increase cognitive load, with a resulting decrease in the availability of cognitive resources for the tasks the individual engages in,” Gay and Castano write.Here is the whole article.

New research suggests sexual objectification hinders some women’s cognitive ability.

By Tom Jacob | April 10, 2010

Guys, here’s something to consider the next time you ogle an attractive woman: Your desirous gaze may be reducing her capacity to think.That’s the startling implication of a research paper titled “My Body or My Mind,” recently published in the European Journal of Social Psychology. It suggests some women who are objectified by men internalize this perception and think of themselves as “a sexual object to be scrutinized.” For reasons that are not entirely clear, this process appears to undermine their cognitive ability.

Psychologists Robin Gay and Emanuele Castano of the New School for Social Research tested this thesis with a clever experiment that mimics and magnifies what many women experience in everyday life. The study participants — 25 women ages 18 to 35 — were told they were recruited to provide information on “the impressions people form about others solely based on their carriage and style of dress.”

Each was videotaped for two minutes — first from the front, then from behind — while they walked up and down a hall. To capture the experience of having their bodies evaluated while their faces (which presumably provide a better reflection of their individual personalities) were ignored, they were filmed exclusively from the neck down.

For half the participants, the person doing the filming was male; for the other half, the camera was held by a woman. “Although there is no doubt that women tend to objectify other women, the sexually objectifying gaze is more likely to come from a man,” the researchers write.

After the filming, each woman watched her video, reinforcing the experience in her mind. She then filled out questionnaires measuring her levels of Trait Self-Objectification (her overall propensity to view herself through the lens of others) and State Self-Objectification (her tendency to view herself through the lens of others when triggered by a specific event, such as being stared at).

To test their cognitive skills, the women were shown a series of random letters or numbers and instructed to reorder them (putting them in alphabetical order for the letters, in ascending order for the numbers). They completed 21 such tasks, which were presented in increasing order of difficulty.

The results: When women with a tendency toward viewing themselves through the lens of others were placed in a situation where they were objectified (that is, they were videotaped by a man), they made a greater number of mistakes on the cognitive test. They did just as well as other women on the easy initial tasks, but had trouble when the difficulty level went up.

After a follow-up study found anxiety and self-esteem levels were not a factor, the researchers concluded their cognitive difficulties “might be due to a split in perspective regarding the self.” (This notion was first described in a 1997 paper by Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts.)

A woman in this situation simultaneously sees herself as a unique individual and a generic sexual being. Dividing the psyche in this uncomfortable way “is likely to increase cognitive load, with a resulting decrease in the availability of cognitive resources for the tasks the individual engages in,” Gay and Castano write.

They suggest further research would be valuable to discover why some women are prone to self-objectification, while others seem protected against it. Gay and Castano’s data suggest about 20 percent of women have a strong propensity toward self-objectification and are thus particularly susceptible to triggers, such as being stared at.

The researchers propose a campaign of awareness and education regarding this phenomenon, which could help women “begin to gain control over, or at least buffer themselves against” its negative cognitive impact. They conclude “it stands to reason that the cumulative effects of objectification on the female body over a lifetime may severely disrupt cognitive processes,” at least among this sizable slice of the population.

This is your brain on wolf whistles.

~ Tom Jacobs is a veteran journalist with more than 20 years experience at daily newspapers. He has served as a staff writer for the Los Angeles Daily News and the Santa Barbara News-Press. His work has also appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune and Ventura County Star.

No comments:

Post a Comment